what effort are we making to contact aliens?

Upon discovering the existence of intelligent life across Earth, the first question we are virtually probable to ask is "How tin nosotros communicate?" As nosotros approach the 50th anniversary of the 1974 Arecibo bulletin—humanity's commencement try to transport out a cannonball capable of being understood past extraterrestrial intelligence—the question feels more urgent than ever. Advances in remote sensing technologies have revealed that the vast majority of stars in our milky way host planets and that many of these exoplanets appear capable of hosting liquid water on their surface—a prerequisite for life as we know information technology. The odds that at least one of these billions of planets has produced intelligent life seem favorable plenty to spend some time figuring out how to say "howdy."

In early March an international team of researchers led by Jonathan Jiang of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory posted a paper on the preprint server arXiv.org that detailed a new design for a bulletin intended for extraterrestrial recipients. The 13-page epistle, referred to as the "Beacon in the Galaxy," is meant to be a basic introduction to mathematics, chemistry and biological science that draws heavily on the design of the Arecibo bulletin and other past attempts at contacting extraterrestrials. The researchers included a detailed plan for the best time of twelvemonth to broadcast the message and proposed a dense ring of stars near the center of our galaxy as a promising destination. Importantly, the transmission likewise features a freshly designed render address that will assistance any alien listeners pinpoint our location in the galaxy then they can—hopefully—boot off an interstellar conversation.

"The motivation for the design was to deliver the maximum corporeality of information about our lodge and the homo species in the minimal amount of message," Jiang says. "With improvements in digital technology, we can exercise much better than the [Arecibo message] in 1974."

Bulletin Nuts

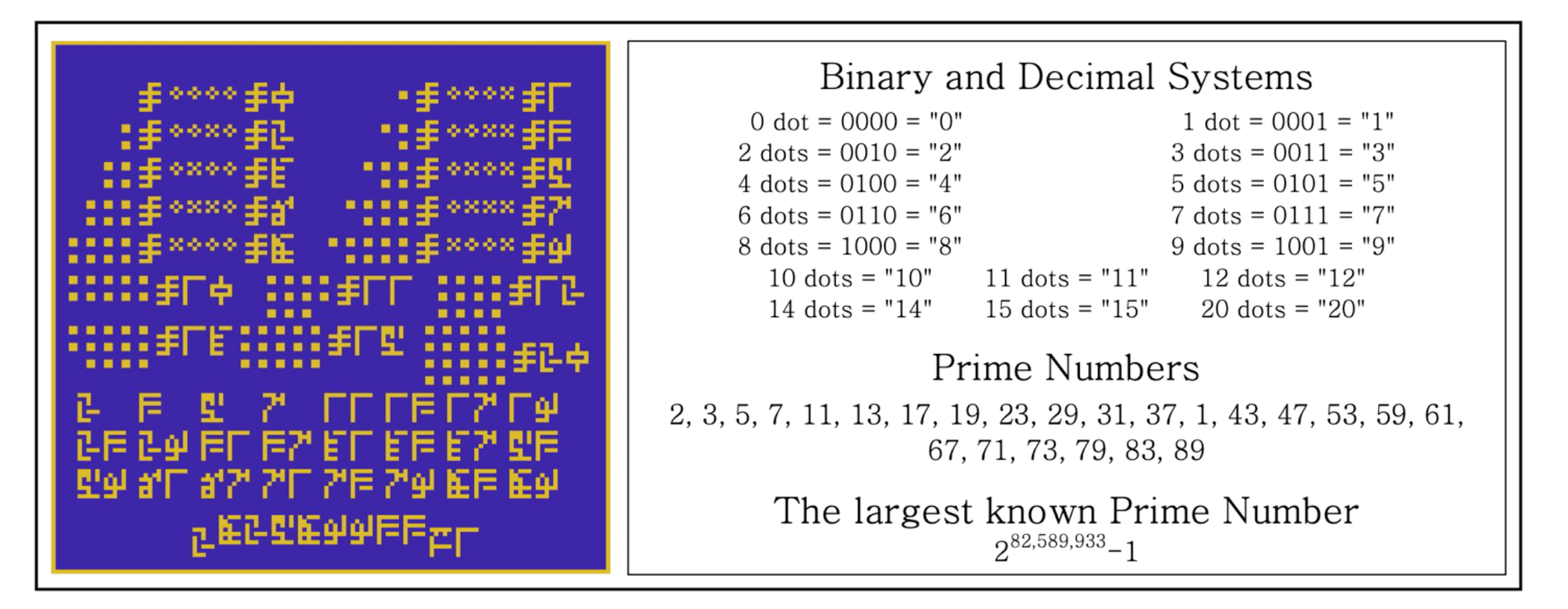

Every interstellar message must address two fundamental questions: what to say and how to say it. Nearly all the messages that humans have circulate into space then far start by establishing common ground with a bones lesson in science and mathematics, two topics that are presumably familiar to both ourselves and extraterrestrials. If a civilisation beyond our planet is capable of building a radio telescope to receive our message, it probably knows a affair or two virtually physics. A far messier question is how to encode these concepts into the communiqué. Man languages are out of the question for obvious reasons, merely and so are our numeral systems. Though the concept of numbers is about universal, the mode we depict them as numerals is entirely arbitrary. This is why many attempts, including "Beacon in the Galaxy," opt to pattern their letter as a bitmap, a way to use binary code to create a pixelated image.

The bitmap design philosophy for interstellar communication stretches back to the Arecibo message. Information technology is a logical approach—the on/off, present/absent nature of a binary seems like it would be recognized by any intelligent species. But the strategy is non without its shortcomings. When pioneering search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) scientist Frank Drake designed a prototype of the Arecibo message, he sent the binary message past mail to some colleagues, including several Nobel laureates. None of them were able to empathize its contents, and only one figured out that the binary was meant to exist a bitmap. If some of the smartest humans struggle to sympathise this grade of encoding a message, it seems unlikely that an extraterrestrial would fare any improve. Furthermore, it is non even clear that infinite aliens volition be able to see the images contained within the message if they do receive information technology.

"One of the key ideas is that, because vision has evolved independently many times on Earth, that ways aliens will have it, too," says Douglas Vakoch, president of METI (Messaging Extraterrestrial Intelligence) International, a nonprofit devoted to researching how to communicate with other life-forms. "But that's a big 'if,' and even if they can see, there is and then much culture embedded in the way we represent objects. Does that mean we should rule out pictures? Absolutely non. Information technology means we should non naively assume that our representations are going to exist intelligible."

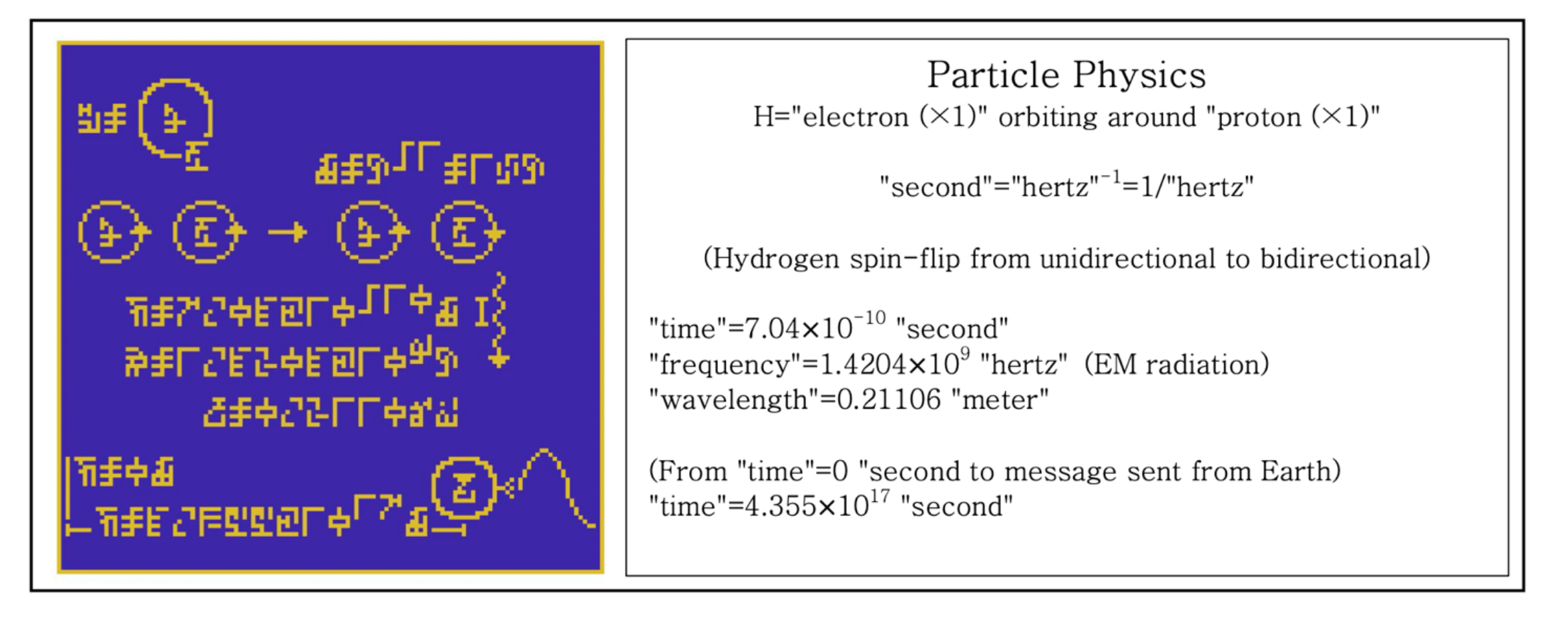

In 2017 Vakoch and his colleagues sent the first interstellar message transmitting scientific information since 2003 to a nearby star. It, too, was coded in binary, but it eschewed bitmaps for a message design that explored the concepts of fourth dimension and radio waves past referring back to the radio wave carrying the message. Jiang and his colleagues chose another path. They based much of their pattern on the 2003 Cosmic Call broadcast from the Yevpatoriaradio telescope in Ukraine. This message featured a custom bitmap "alphabet" created by physicists Yvan Dutil and Stéphane Dumas as a protoalien language that was designed to be robust confronting manual errors.

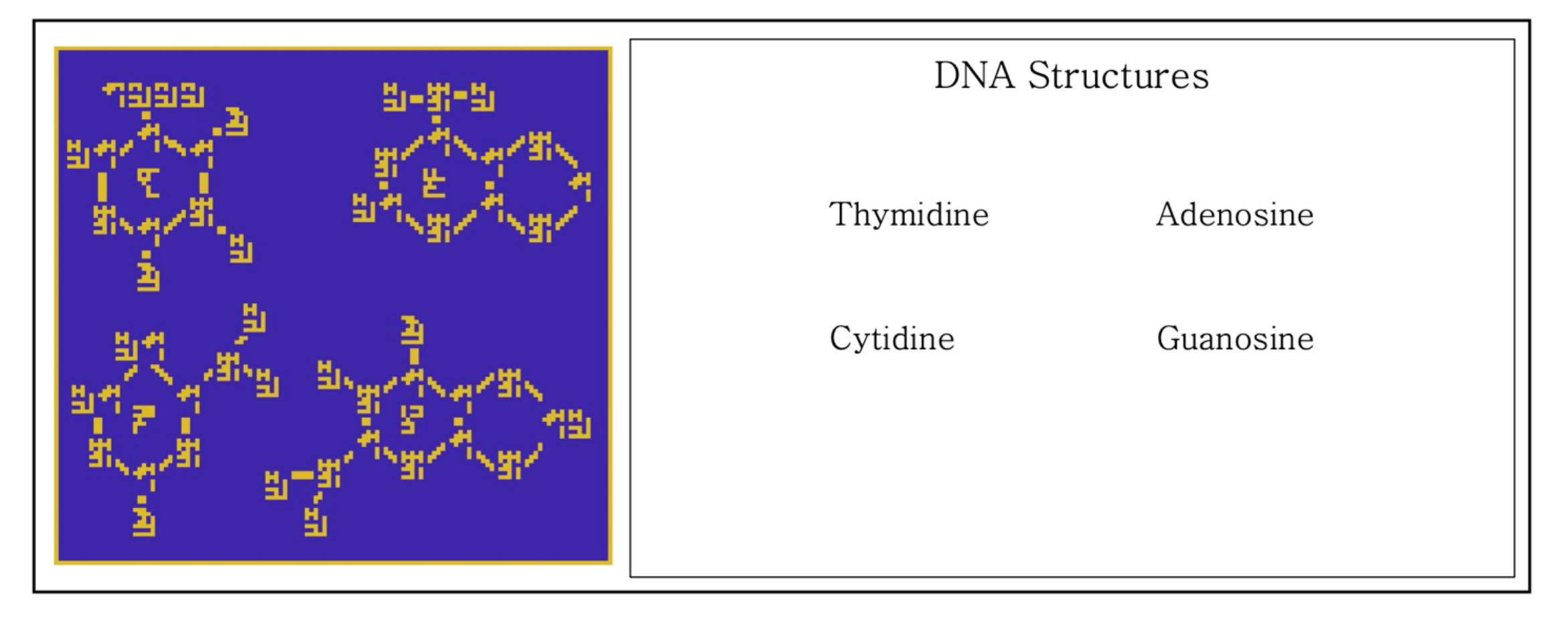

After an initial manual of a prime number to mark the bulletin as artificial, Jiang's message uses the same conflicting alphabet to innovate our base of operations-10 numeral arrangement and basic mathematics. With this foundation in place, the message uses the spin-flip transition of a hydrogen cantlet to explain the idea of time and mark when the transmission was sent from World, innovate common elements from the periodic tabular array, and reveal the construction and chemical science of DNA. The last pages are probably the most interesting to extraterrestrials only also the to the lowest degree probable to be understood considering they assume that the recipient represents objects in the same fashion that humans do. These pages feature a sketch of a male and female person human, a map of World's surface, a diagram of our solar system, the radio frequency that the extraterrestrials should use to respond to the message and the coordinates of our solar system in the galaxy referenced to the location of globular clusters—stable and tightly packed groups of thousands of stars that would likely exist familiar to an extraterrestrial anywhere in the galaxy.

"We know the location of more than fifty globular clusters," Jiang says. "If in that location's an avant-garde civilization, we bet that, if they know astrophysics, they know the globular cluster locations as well, and so we can utilise this as a coordinate to pinpoint the location of our solar system."

To Send or Not?

Jiang and his colleagues propose sending their bulletin from either the Allen Telescope Array in northern California or the Five-Hundred-Meter Aperture Spherical Radio Telescope (FAST) in China. Since the contempo destruction of the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico, these 2 radio telescopes are the only ones in the globe that are actively courting SETI researchers. At the moment, though, both telescopes are only capable of listening to the creation, not talking to it. Jiang acknowledges that outfitting either telescope with the equipment required to transmit the message volition non be trivial. Merely doing so is possible, and he says that he is in ongoing discussions with researchers at FAST about making it happen.

If Jiang and his colleagues go a chance to transmit their message, they calculated that it would be all-time to do and then sometime in March or October, when Globe is at a 90-degree angle betwixt the sun and its target at the center of the Milky way. This would maximize the risk that the missive would not get lost in the background racket of our host star. But a far deeper question is whether we should exist sending a message at all.

Messaging extraterrestrials has always occupied a controversial position in the broader SETI community, which is mostly focused on listening for alien transmissions rather than sending out our ain. To detractors of "active SETI," the exercise is a waste of time at best and an existentially unsafe gamble at worst. There are billions of targets to choose from, and the odds that we send a message to the right planet at the correct time are dismally low. Plus, we take no idea who may be listening. What if we give our address to an alien species that lives on a nutrition of bipedal hominins?

.png)

"I don't live in fear of an invading horde, simply other people do. And just because I don't share their fearfulness doesn't make their concerns irrelevant," says Sheri Wells-Jensen, an associate professor of English at Bowling Dark-green State University and an expert on the linguistic and cultural bug associated with interstellar message blueprint. "Just considering information technology would exist difficult to accomplish global consensus on what to transport or whether we should send doesn't mean nosotros shouldn't practise information technology. It is our responsibility to struggle with this and include as many people as possible."

Despite the pitfalls, many insist that the potential rewards of agile SETI far outweigh the risks. Outset contact would be one of the most momentous occasions in the history of our species, the argument goes, and if we merely await around for someone to call the states, it may never happen. Equally for the chance of annihilation past a malevolent infinite alien: We blew our cover long ago. Any extraterrestrial capable of traveling to Globe would be more than capable of detecting evidence of life in the chemical signatures of our atmosphere or the electromagnetic radiation that has been leaking from our radios, televisions and radar systems for the past century. "This is an invitation to all people on World to participate in a discussion about sending out this bulletin," Jiang says. "We hope, by publishing this paper, we tin encourage people to remember near this."

Source: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/researchers-made-a-new-message-for-extraterrestrials/

0 Response to "what effort are we making to contact aliens?"

Post a Comment